From poems to paintings, several students were recognized during the second annual Black Excellence in the Arts Awards Ceremony Feb. 22.

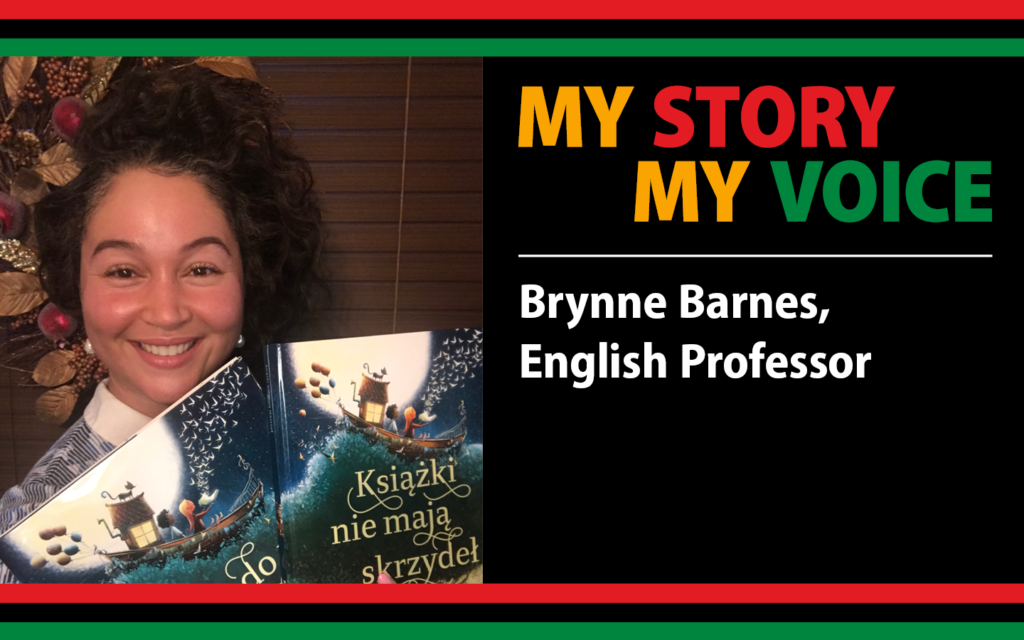

When it comes to artistic expression, Brynne Barnes compared the work of writers to those who tend gardens.

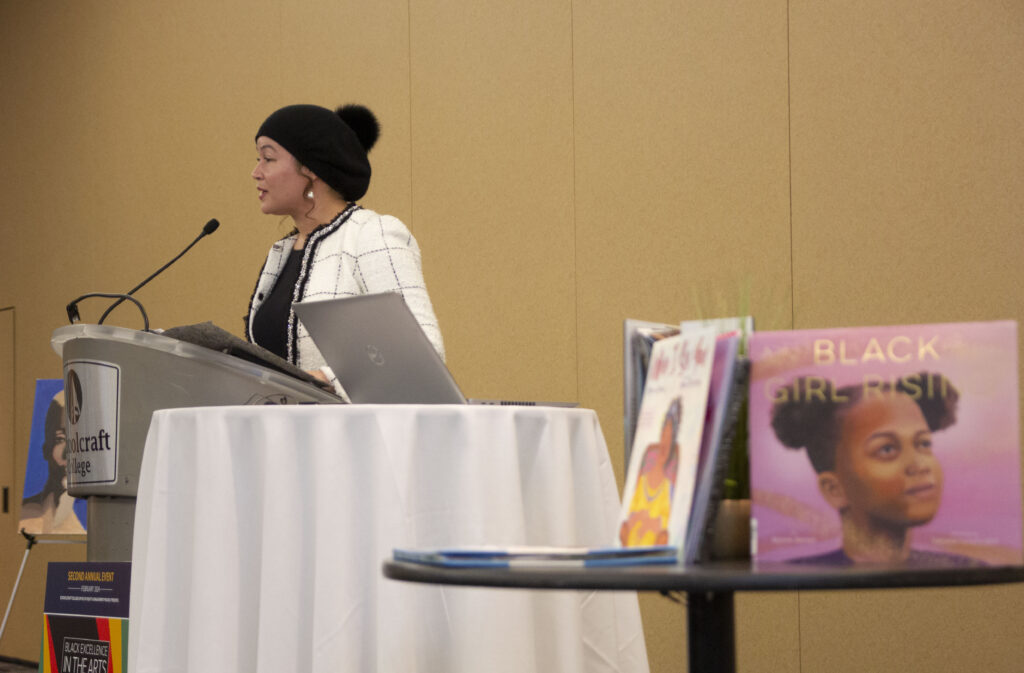

“A writer creates gardens with words. Ideas are like fireflies: they’re bright, they’re beautiful and they’re fleeting. Dreams are the same way: they must be captured quickly, or they’re gone,” said Barnes, an English instructor at Schoolcraft College and an award-winning author. “It takes attention, dedication. And by doing what is necessary with passion and willingness, it transforms. That is how we write history. That is how we create ourselves and the world around us.”

Barnes’s remarks came as she addressed students being recognized for their art during the second Black Excellence in the Arts Award Ceremony.

The event – held Feb. 22 in the DiPonio Room of the Vistatech Center and put on by the College’s Office of Equity and Engagement – celebrated excellence in the arts, with students submitting pieces in various mediums.

The following students received accolades for their work:

Artwork

1st place – Quinlan Brooks

Honorable mention – Sara Meeks

Essays

1st Place – Matthew Morrow

Honorable mention – Shelby Knott

Poems

1st Place – Gar Willoughby

Honorable mention – Zahraa Alrafish

The reception was lined with much of the artwork submitted for consideration. It showcased the theme for this year’s Black History Month, which is “African Americans and the Arts.”

Other speakers at this year’s event included State Rep. Stephanie A. Young, Livonia City Councilwoman Carrie Budzinski and Delia Upshaw, the chairwoman for the Livonia Equity & Anti-Racism Network.

Also speaking was Dr. Glenn Cerny, president of Schoolcraft College. Cerny said having students flourish in the arts helps make the College a better place not just for learning but for connecting with the community.

“The arts are a part of this culture,” he said. “That’s important to the Schoolcraft College community, and when I say community, that’s what I mean. We’re not just a college, we’re a community.”

Learn more and view event photos

Feature Image Caption: Student Quinlan Brooks speaks while his artwork, three portraits, are on display in the background.